History is replete with the spilling of innocent blood.

Its Biblical beginnings being the story of Cain and Abel (Genesis 4). Notice God’s dialogical approach to evil. It is identical to the prototype text offered to us in Genesis 2, where we witness the primordial sin of Adam and Eve.

God does not ‘point the finger’ at our first parents, rather he asks them questions. The questions are for their benefit, helping them understand what has actually happened. This is ‘Parenting 101.’ Fit for purpose in the 21st Century.

Jesus of Nazareth was murdered, and his innocent blood flows freely in and over each one of us to this day.

He lived in a village not even mentioned in the Old Testament and worked away with his human father Joseph, and his mother Mary, involved and invested in manual work for 25 years.

His public life of three years ended in total disgrace – crucified with criminals outside the city, but not before one of them declared, ‘This man has done no wrong’ (Luke 23).

Jesus was innocent. No sin – no division – resided in him.

Jesus is unique. There has never been anyone like him, nor will there ever be:

For our sake he made him to be sin, who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God (2 Cor. 5:21).

It is worth repeating an important theological insight, one explicated in the previous conference:

The Father and Jesus are intimately involved in the passion. We find an echo in the passion narrative of Abraham. But whereas God did not really ask Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac, God asked himself to give us his Son.

Let us forget the nonsensical argument that somehow Jesus was placating the anger of the Father in his passion. That is nothing but crass theology.

We must take at face value – and then explore with faith and reason – the following texts:

God so loved the world that he gave his only Son so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but have eternal life (John 3:16-17).

God who did not spare his own Son, but gave him up for us all (Romans 8:32).

Think of a gift. It has two dimensions: It is given generously and then graciously received.

Think of a mother and father letting their son or daughter loose in the big wide-world. They must honour freedom, but it is not risk-free.

Think of Jesus’ death in this way: the logical consequence of believing in the truth is that I am prepared to die for the truth. Jesus, the Word spoken by the Father – now made Flesh – lives out the consequence of his name.

Brendan Byrne, SJ, leads us magnificently in a profound faith reflection. It begins with the preamble to the passion and resurrection of Jesus found in Matthew 26.

We have the conspiracy against Jesus (Matthew 26:3-5) by the chief priests, but they fear ‘a riot among the people.’ We have Judas who betrays Jesus for thirty silver pieces (Matthew 26:17-19).

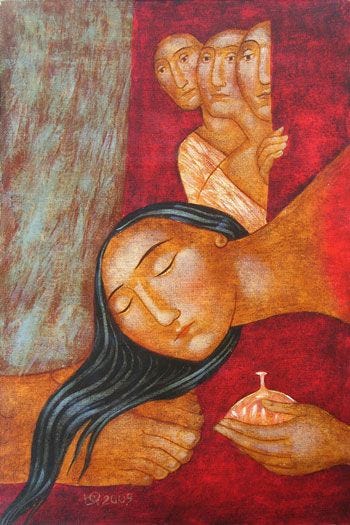

Sandwiched – a literary technique common at the time – between these two scenes is the unnamed woman who anoints Jesus at Bethany (Matthew 26:6-13).

She cracks open an alabaster jar – the only way to get the ointment out of the container – and anoints Jesus by pouring it on his head as he sits at table. The ointment is costly, far more valuable than thirty pieces of silver.

Jesus responds to the apostles, who think the money should be spent on the poor (ordinarily a good thing to do, but misplaced in this case):

Why do you trouble the woman? She has performed a beautiful service (ergon … kalon) for me. For you always have the poor with you, but you will not always have me.

By pouring this ointment on my body, she has prepared me for burial.

The Greed word ‘kalos’ means ‘beautiful,’ and carries the connotation of ‘appropriate or fitting for this occasion:’

In other words, this unnamed woman understood the cost of the passion of Jesus, demonstrated by her extravagant – beautiful – use of the ointment.

Contrast this with Judas who sells Jesus cheaply. She, not he, has understood the infinite worth of Jesus. An early Second Century Homily rallies around such thinking:

Brothers and sisters, we ought to regard Jesus Christ as God and judge of the living and the dead. We should not hold our Saviour in low esteem, for if we esteem him but little, we may hope to obtain but little from him.

Moreover, people who hear these things and think them of small importance commit sin, and we ourselves sin if we do not realise what we have been called from, who has called us, and to what place, and how much suffering Jesus Christ endured on our account (Cap. 1, 1-2,7: Funk 1, 145-149).

Having the right disposition as we begin to hear the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus proclaimed, or as we read it meditatively, is crucial. St. Benedict, in the preamble of his great rule for religious life, puts it best: ‘Listen with the ears of your heart.’

We should note:

That Matthew does not include Mark’s comment that ‘she has done what she could.’

We are only human beings and ‘we can only do what we can do’ with our fragile and limited human resources.

We simply try our best to follow Jesus in his passion, death and resurrection and God will be happy with that.

One final and critical point in this beautiful narrative:

The woman is unnamed – and deliberately so it seems.

Matthew wants us to insert ourselves in her place. We take the alabaster jar and crack it open, pouring the contents all over Jesus, who is precious to us.

Amen.

Q. How much do you love and value Jesus, and what beautiful service are you prepared to do for him?

Cheap Betrayal

Extravagant Love

Powerful reflection

Thankyou

Beautiful reflection. Powerful imagery.