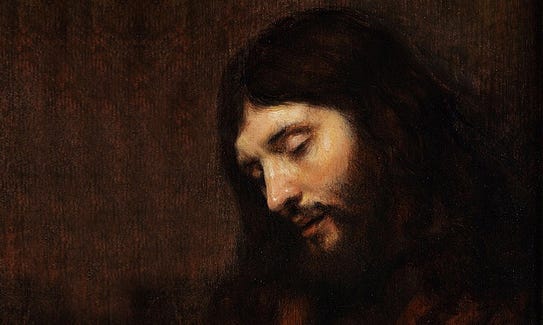

Jesus asks, ‘Who do people say the Son of Man is?’ Peter nails it:

You are the Christ, the Son of the living God (Matthew 16).

Jesus reveals another beatitude:

Blessed are you Simon Bar-Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven.

Why, like Peter, do we believe Jesus to be the Son of God and the Son of Man?

I bless you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, that you have hidden these things from the wise and clever and revealed them to little children, yes, Father, for such was your gracious will (Matthew 11:25-26).

Our faith is tangible because of the sublime activity of the Father. He it is who reveals to us – his ‘little ones’ – the mysteries of the Kingdom.

Now for the ‘watershed moment.’

Jesus teaches that he is going to suffer greatly, be killed, and be raised up on the third day. He does this in three ‘passion predictions’ (Matthew 16:21-23; 17: 22-23; 20:20-23).

Peter especially, but all of the apostles too, do not understand these predictions. How is it that the messiah will suffer and die? What kind of messiah is Jesus?

The ‘watershed moment’ includes the transfiguration of Jesus (Matthew 17:1-8). It is a glorious and momentous revelation. We hear the Father declare, ‘This is my Son, the Beloved, with him I am well pleased. Listen to him.’

We must listen to Jesus, for he impresses upon us that an impending disgrace, torture and death awaits him. These events are unavoidable, yet it is not easy for us to receive this truth.

After the third passion prediction, we encounter two scenes, especially fit for those in authority, no matter what form it takes.

The mother of the sons of Zebedee requests that her sons sit at the right and left of Jesus in his Kingdom (Matthew 20:20-23).

However, Jesus is inaugurating a new family for a Kingdom not of this world. The sons are asked if they can drink the cup (‘painful destiny’) that Jesus is about to drink. They respond positively yet naively. At this moment, Jesus reveals the manner of his dying:

You will indeed drink my cup, but to sit at my right hand and at my left, this is not mine to grant, but it is for those for whom it has been prepared by my Father.

We are invited to think more deeply about the Father’s activity in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus:

This is very revealing. For Jesus is not going to die in a calculating way; rather he surrenders himself in trust (‘hands over’) to the Father, who has prepared it all.

In other words, the Father and Son are intimately involved in the salvation of the world:

It is a tripartite salvation, involving suffering, death and resurrection. Theology calls this the Paschal Mystery – the ‘Passing-over’ Mystery.

The Father prepares the mystery. The Son enters the mystery through suffering and death. The Father accepts his Son’s surrender by ‘raising him from the dead’ (Acts 10:40).

If we focus just on the suffering and death of Jesus alone, then, of course we will be tempted to view Jesus’ death in a ‘calculating way.’

Yet it is ‘tripartite salvation.’

The Father raises his Son from the dead after his suffering and death. In this way, he gifts the world with his Son. Suffering and death are no longer the final word. They form part of the ‘passage-way’ to new, resurrected life with the Son. Suffering and death henceforth take on redemptive meaning with the grace of the Spirit.

The second scene unfolds immediately. The other apostles are angry with the two brothers. Jesus responds by declaring that authority in Christian communities is fundamentally different to worldly authority:

Whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant (diakonos), and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave (doulos), just as the Son of Man came not to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom (lytros) for many (Matthew 20-24-28).

What is the meaning of the Greek word lytros?

It means freedom from oppression. In the ancient world wars were prevalent and soldiers were captured by opposing sides. They became slaves until someone ‘bought them back at a price.’

Jesus will pay the price (cost) of suffering to liberate us from our chief form of oppression – our sinfulness, and its consequences, our death.

Jesus will die for ‘the many’ – a Hebrew word and idiom meaning, ‘others apart from oneself.’

The text evokes Isaiah 53:11-12. We might take time to read this passage, proclaimed each Good Friday. It aids interpretation of Jesus’ Paschal Mystery.

Jesus, our great high priest (Hebrews 4:14), performs the most degrading act of service in his salvific death. Evocatively, we are invited to think about the child abuse crisis in the Church:

Yes, we have witnessed in the child sexual abuse crisis a horrific abuse of authority.

But the way forward is not to rail against clericalism, but to affirm that the dignity of being a priest, after the example of Jesus, is a call to perform the most humble acts of service for one’s brothers and sisters.

This call is especially present when the priest says, not in his own person, but in Persona Christi, ‘This is my body; This is my blood.’

When we speak of authority, we tend to think of ‘grandiose-authority,’ but ‘natural-authority’ is widespread and very important to the cultural fabric of society.

Parents, teachers, nurses and doctors, exercise very important forms of authority. All of them benefit from Jesus’ teaching and example.

Amen.

Q. How will we exercise the authority that has been given to us?